WHY AFRICAN BOARDERS IS A MESS

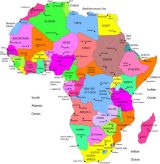

First, it is worth mentioning that only a third of its 83,000km of land borders is properly demarcated. The African Union (AU) is helping states to tidy up the situation, but it has repeatedly pushed back the deadline for finishing the job. It was meant to be done in 2012, then 2017, and now, it was announced in 2022. Why is it so hard to demarcate Africa’s borders and why does it matter?

Most pre-colonial borders were fuzzy. Europeans changed that, carving up territory by drawing lines on maps. ‘We have been giving away mountains and rivers and lakes to each other,” mused the British prime minister, Lord Salisbury, in 1890, “only hindered by the small impediments that we never knew where the mountains and rivers and lakes were.” It took 30 years to settle the boundary between Congo and Uganda, for example, after the Belgians twice got their rivers muddled up. In 1964 independent African states, anxious to avoid conflict, agreed to stick with the colonial borders. But they made little effort to mark out frontiers on the ground.

Before European colonization. 7th to 16th century

Colonialism had a destabilizing effect on a number of ethnic groups that is still being felt in African politics. Before European influence, national borders were not much of a concern, with Africans generally following the practice of other areas of the world, such as the Arabian Peninsula, where a group’s territory was congruent with its military or trade influence. The European insistence of drawing borders around territories to isolate them from those of other colonial powers often had the effect of separating otherwise contiguous political groups, or forcing traditional enemies to live side by side with no buffer between them. For example, although the Congo River appears to be a natural geographic boundary, there were groups that otherwise shared a language, culture or other similarity living on both sides. The division of the land between Belgium and France along the river isolated these groups from each other. Those who lived in Saharan or Sub-Saharan Africa and traded across the continent for centuries often found themselves crossing borders that existed only on European maps.

European territorial claims on the African continent in 1914

In the mid-nineteenth century, European explorers became interested in exploring the heart of the continent and opening the area for trade, mining and other commercial exploitation. In addition, there was a desire to convert the inhabitants to Christianity. The central area of Africa was still largely unknown to Europeans at this time . A prime goal for explorers was to locate the source of the River Nile. Expeditions by Burton and Speke (1857-1858) and Speke and Grant (1863) located Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria. The latter was eventually proven as the main source of the Nile. With subsequent expeditions by Baker and Stanley, Africa was well explored by the end of the century and this was to lead the way for the colonization which followed.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-85

The Berlin Conference of 1884-85 regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany’s sudden emergence as an imperial power. Called for by Portugal and organized by Otto von Bismarck, the first Chancellor of Germany, its outcome, the General Act of the Berlin Conference, is often seen as the formalization of the Scramble for Africa. The conference ushered in a period of heightened colonial activity on the part of the European powers, while simultaneously eliminating most existing forms of African autonomy and self-governance. From 1885 the scramble among the powers went on with renewed vigor, and in the 15 years that remained of the century, the work of partition, so far as international agreements were concerned, was practically completed.

The African continent in 1914

In the late nineteenth century, the European imperial powers engaged in a major territorial scramble and occupied most of the continent, creating many colonial nation states, and leaving only two independent nations: Liberia, an independent state partly settled by African Americans; and Orthodox Christian Ethiopia (known to Europeans as “Abyssinia”).

In nations that had substantial European populations, for example Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Angola, Mozambique, Kenya and South Africa, systems of second-class citizenship were often set up in order to give Europeans political power far in excess of their numbers. In the Congo Free State, personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium, the native population was submitted to inhumane treatment, and a near slavery status assorted with forced labor. However, the lines were not always drawn strictly across racial lines. In Liberia, citizens who were descendants of American slaves had a political system for over 100 years that gave ex-slaves and natives to the area roughly equal legislative power despite the fact the ex-slaves were outnumbered ten to one in the general population.

Europeans often altered the local balance of power, created ethnic divides where they did not previously exist, and introduced a cultural dichotomy detrimental to the native inhabitants in the areas they controlled. For example, in what are now Rwanda and Burundi, two ethnic groups Hutus and Tutsis had merged into one culture by the time German colonists had taken control of the region in the nineteenth century. No longer divided by ethnicity as intermingling, intermarriage, and merging of cultural practices over the centuries had long since erased visible signs of a culture divide, Belgium instituted a policy of racial categorization upon taking control of the region, as racially based categorization and philosophies were a fixture of the European culture of that time. The term Hutu originally referred to the agricultural-based Bantu-speaking peoples that moved into present day Rwanda and Burundi from the West, and the term Tutsi referred to Northeastern cattle-based peoples that migrated into the region later. The terms described a person’s economic class; individuals who owned roughly 10 or more cattle were considered Tutsi, and those with fewer were considered Hutu, regardless of ancestral history. This was not a strict line but a general rule of thumb, and one could move from Hutu to Tutsi and vice versa.

The Belgians introduced a racialized system; European-like features such as fairer skin, ample height, narrow noses were seen as more ideally Hamitic, and belonged to those people closest to Tutsi in ancestry, who were thus given power amongst the colonized peoples. Identity cards were issued based on this philosophy.

War world I

During World War I, there were several battles between the United Kingdom and Germany, the most notable being the Battle of Tanga, and a sustained guerrilla campaign by the German General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. After World War I, the former German colonies in Africa were taken over by France and the United Kingdom.

During this era a sense of local patriotism or nationalism took deeper root among African intellectuals and politicians. Some of the inspiration for this movement came from the First World War in which European countries had relied on colonial troops for their own defense. Many in Africa realized their own strength with regard to the colonizer for the first time. At the same time, some of the mystique of the “invincible” European was shattered by the barbarities of the war. However, in most areas European control remained relatively strong during this period.

In 1935, Benito Mussolini’s Italian troops invaded Ethiopia, the last African nation not dominated by a foreign power.

World War II

Africa, especially North Africa, was an important theater of war. French colonies in Africa supported the Free French. Many black Africans were conscripted to fight against the Germans. Italy had a presence in Libya and also in Ethiopia. In the North African campaign, the Deutsches Afrika Korps under General Erwin Rommel were eventually defeated at the Second Battle of El Alamein. The Allies used North Africa as a jumping off point for the invasions of Italy and Sicily in 1943. Germany wanted to expand its interests in Africa, while Britain was anxious to protect its interests in Egypt and the route to the east.

Postcolonial era: 1945-1990

Today, Africa contains 53 countries so called “independent and sovereign countries” , most of which still have the borders drawn during the era of European colonialism.

Decolonization

Vincent Khapoya notes the significant resistance imperialist powers faced to their domination in Africa. Technical superiority enabled conquest and control. Africans recognized the value of European education in dealing with Europeans in Africa. They noticed the discrepancy between Christian teaching of universal brotherhood and the treatment they received from missionaries. Some established their own churches. Africans also noticed the unequal evidences of gratitude they received for their efforts to support Imperialist countries during the world wars: “Many British veterans were rewarded for their part in saving Britain and her empire with generous pensions and offers of nearly free land in the colonies.

The African soldiers were given handshakes and train tickets for the journey back home. They could keep their khaki uniforms and nothing else. These African soldiers, after returning home, were willing to use their new skills to assist nationalist movements fighting for freedom that were beginning to take shape in the colonies.”

Decolonization in Africa started with Libya in 1951 (Liberia, South Africa, Egypt, and Ethiopia were already independent). Many countries followed in the 1950s and 1960s, with a peak in 1960 with the independence of a large part of French West Africa. Most of the remaining countries gained independence throughout the 1960s, although some colonizers (Portugal in particular) were reluctant to relinquish sovereignty, resulting in bitter wars of independence which lasted for a decade or more. The last African countries to gain formal independence were Guinea-Bissau from Portugal in 1974, Mozambique from Portugal in 1975, Angola from Portugal in 1975, Djibouti from France in 1977, Zimbabwe from Britain in 1980, and Namibia from South Africa in 1990. Eritrea later split off from Ethiopia in 1993.

Effects of decolonization

In most British and French colonies, the transition to independence was relatively peaceful. Some settler colonies however were displeased with the introduction of democratic rule. In the aftermath of decolonization, Africa displayed political instability, economic disaster, and debt dependence. In all cases, measures of life quality (such as life expectancy) fell from their levels under colonialism, with many approaching precolonial levels. Political instability occurred with the introductions of Marxist and capitalist influence, along with continuing friction from racial inequalities. Inciting civil war, black nationalist groups participated in violent attacks against white settlers, trying to end white minority rule in government.

Decolonized Africa has lost many of its social and economic institutions and to this day shows a high level of informal economic activity. In another result of colonialism followed by decolonization, the African economy was drained of many natural resources with little opportunity to diversify from its colonial export of cash crops. Suffering through famine and drought, Africa struggled to industrialize its poverty stricken work force without sufficient funds.

To feed, educate, and modernize its masses, Africa borrowed large sums from various nations, banks and companies. In return, lenders often required African countries to devalue their currencies and attempted to exert political influence within Africa. The borrowed funds, however, did not rehabilitate the devastated economies. Since the massive loans were usually squandered by the mismanagement of corrupt dictators, social issues such as education, health care and political stability have been ignored

The by-products of decolonization, including political instability, border disputes, economic ruin, and massive debt, continue to plague Africa to this present day. Due to on-going military occupation, Spanish Sahara (now Western Sahara), was never fully decolonized. The majority of the territory is under Moroccan administration; the rest is administered by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic.

In 2005, the European Union agreed to a Strategy for Africa including working closely with the African Union to promote peace, stability and good governance. However, inter-tribal war in Rwanda during the genocide of 1994, in Somalia over more than 20 years, and between Arabs and non-Arabs in Sudan indicates to some observers that Africa is still locked in tribalism and far from ready to assume its place at the global table of mature, stable and democratic states.

The Cold War in Africa

Africa was an arena during the Cold War between the U.S., Soviet Union, and even China and North Korea. Communist and Marxist groups, often with significant outside assistance, vied for power during various civil wars, such as that in Angola, Mozambique and Ethiopia. A Marxist-oriented president, Julius Nyerere, held in power in Tanzania from 1964-85, while from 1955-75, Egypt depended heavily on Soviet military assistance. The communist powers sought to install pro-communist or communist governments, as part of their larger geostrategy in the Cold War, while the U.S. tended to maintain corrupt authoritarian and monarch rulers (such as Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire and Haile Selassie King of Ethiopia) as the price to keep countries in the pro-democracy camp.

Pan-Africanism

In 1964, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) was established with 32 member states. It aimed to:

1. Promote the unity and solidarity of the African states;

2. Coordinate and intensify their cooperation and efforts to achieve a better life for the peoples of Africa;

3. Defend their sovereignty, territorial integrity and independence;

4. Eradicate all forms of colonialism from Africa; and,

5. Promote international cooperation, having due regard to the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

In 2002, the OAU was succeeded by the African Union. Several UN peacekeeping missions have been either entirely composed of African Union forces, or they have represented a significant component as the strategy of Africans policing Africa develops. These include Liberia in 2003; Burundi in 2003; Sudan in 2004. Others speculate that since the U.S. withdrew its UN peacekeepers from Somalia-after 18 soldiers died, with 70 wounded, in Mogadishu, Somalia in October 1993 the Western powers have been very reluctant to commit ground forces in Africa. This may explain why the international community failed to intervene during the Rwandan Genocide of 1994, stationing less than 300 troops there with orders “only to shoot if shot at.”

To summarized what happened in past in Africa can’t been change but future generation and future leaders of Africa can change things around. African can’t keep blaming foreigners for causes of their suffering and lack of development in Continent. If you look in deep, African leaders or African presidents are partially to blame for suffering of African people. African leaders are putting themselves first to stay in power then to stand for what it’s right for their people. These are best lessons for African future generation and leaders to learn from past history of Africa itself and to try to have better Africa continent in future!